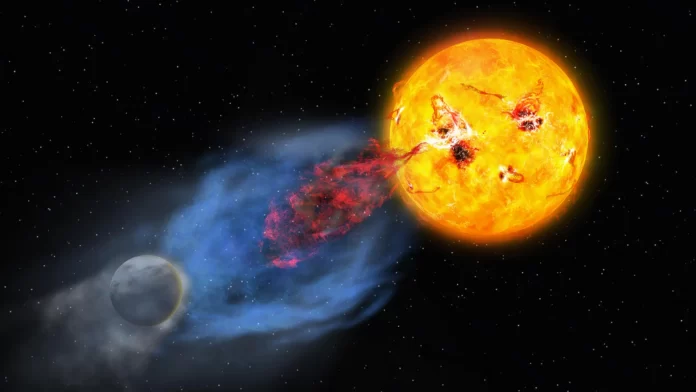

Although we rarely notice from Earth, the Sun is continuously hurling enormous clouds of charged plasma into space. These events, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), often occur alongside sudden bursts of light called solar flares. When particularly strong, CMEs can stretch far enough to disturb Earth’s magnetic field, producing dazzling auroras and sometimes triggering geomagnetic storms that disrupt satellites or even power grids.

Scientists believe that billions of years ago, when the Sun and Earth were both young, solar activity was far more intense than it is today. Powerful CMEs during that period may have influenced the conditions that allowed life to emerge and evolve. Studies of young Sun-like stars — used as stand-ins for our own star’s early years — show that these stars often unleash flares far stronger than any recorded from the modern Sun.

Reconstructing Ancient Solar Explosions

Massive eruptions from the early Sun likely had dramatic effects on the atmospheres of Earth, Mars, and Venus. Yet researchers still do not fully understand how closely these stellar outbursts resemble today’s CMEs. While scientists have recently observed cooler plasma components of CMEs from the ground, detecting the fast-moving, high-energy events expected in the past has proven much more difficult.

To explore this question, an international research team led by Kosuke Namekata of Kyoto University set out to determine whether young Sun-like stars generate CMEs similar to those of our own Sun.

“What inspired us most was the long-standing mystery of how the young Sun’s violent activity influenced the nascent Earth,” says Namekata. “By combining space- and ground-based facilities across Japan, Korea, and the United States, we were able to reconstruct what may have happened billions of years ago in our own solar system.”

The researchers conducted simultaneous ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope and optical observations from ground-based telescopes in Japan and Korea. Their subject was the young Sun-like star EK Draconis. Hubble measured ultraviolet light from extremely hot plasma, while the ground-based observatories tracked cooler hydrogen gas through the Hα line. This coordinated, multi-wavelength approach enabled the team to capture both the hot and cool parts of a CME as it unfolded.

Evidence of a Multi-Temperature Solar Eruption

The observations revealed the first-ever evidence of a multi-temperature CME from EK Draconis. The team discovered that plasma heated to about 100,000 degrees Kelvin was expelled at speeds of 300 to 550 kilometers per second (~670,000 to 1,230,000 miles per hour). Roughly ten minutes later, cooler gas around 10,000 degrees was launched at about 70 kilometers per second (~160,000 miles per hour). The high-temperature plasma carried significantly more energy, indicating that frequent and powerful CMEs in the past could have produced strong shocks and energetic particles capable of reshaping or stripping early planetary atmospheres.

Other studies support the idea that energetic solar events and their resulting particles may have triggered chemical reactions that produced biomolecules and greenhouse gases — key ingredients for sustaining life. This finding therefore deepens our understanding of how solar activity may have created the environmental conditions necessary for life to appear on early Earth, and possibly on other planets as well.

The scientists emphasized that their success depended on global collaboration and precise coordination between space- and ground-based observatories.

“We were happy to see that, although our countries differ, we share the same goal of seeking truth through science,” says Namekata.